Workers

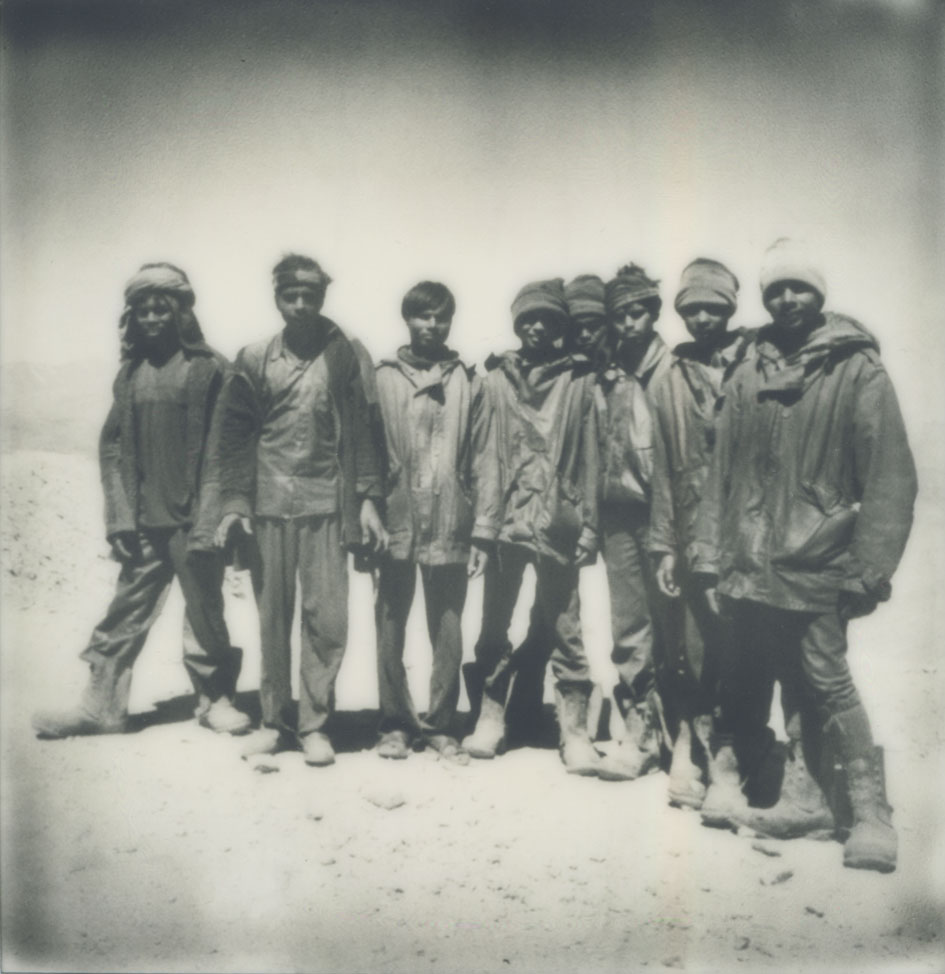

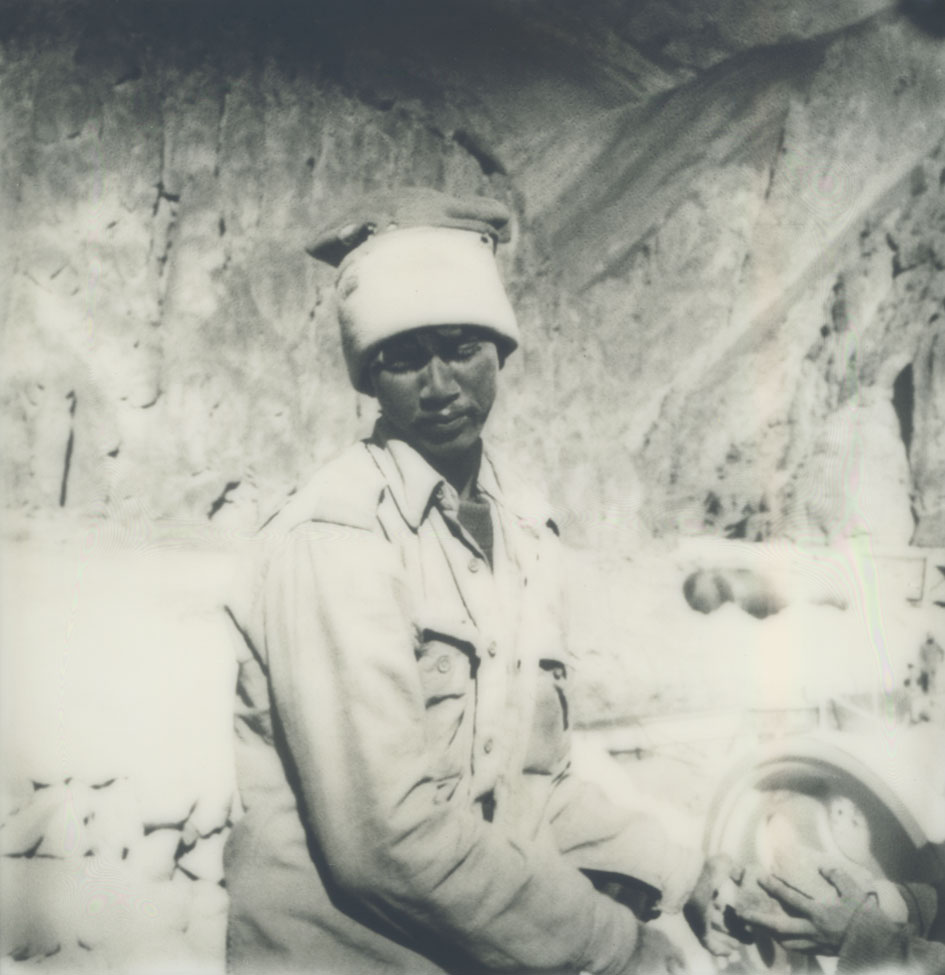

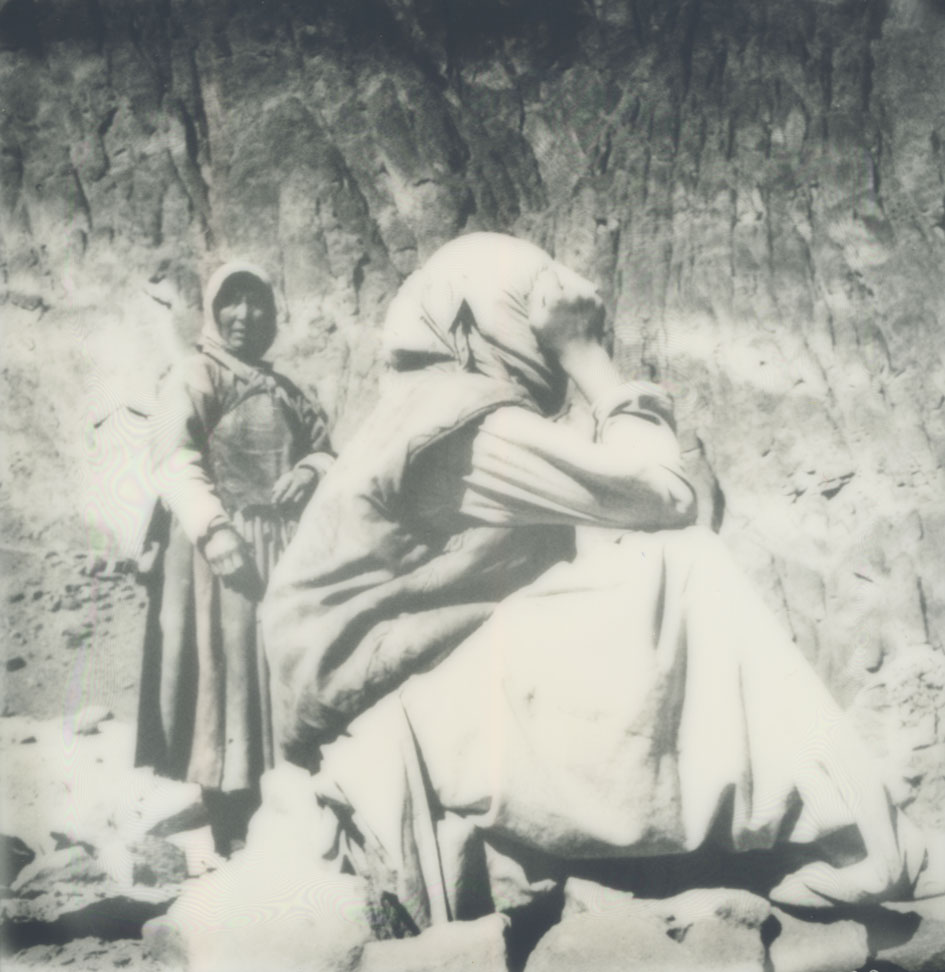

The Manali to Leh road, which travels through India’s Himalayan region of Ladakh, known as the land of high passes, is amongst the highest in the world. Shut off for seven months of the year, the summer sees the arrival of tens of thousands of migrant workers from some of India’s poorest regions including Bihar, Jharkhand and West Bengal, who come to build and maintain the roads recently revealed from beneath a blanket of snow. Men, women and children struggle against harsh conditions with only basic tools; at altitudes of over 5,000m oxygen is thin and night time temperatures are below freezing with frequent snowfall, the workers are accommodated in basic tent structures and suitable clothing and safety apparatus are almost entirely absent.

In the spring of 2005, curious about the most northern borders of India, I took this road that wound itself into and over these great passes of the Himalayas. Some days I travelled on foot, others I would thumb a lift from the trucks that carried supplies, tools or even road workers heading in the same direction; occasionally I would be invited to sit within the relative warmth of the cabin which overflowed and glimmered with the imagery of gods and the trinkets offered to these deities for safe passage along this precipitous road, but most often I’d find myself sat on top of these trucks watching in awe as I crossed this landscape from my exposed yet panoramic vantage point, gripping onto the rails at hair pin bends as I caught glimpses of burnt out shells and carcasses of fallen vehicles in the deep ravines below, contemplating if I’d be able to jump off fast enough if the same was to happen to us.

As the journey progressed out of the forested foothills and crossed into the higher regions of the Himalayas the landscape became dryer, harder and barren, yet held a beauty I had not anticipated - how the light would shine brighter as we got higher and the clouds would cast impenetrable dark shadows like black lakes traversing the landscape as the moisture disappeared from the atmosphere. The wind was biting, my cheeks quickly became red and cracked and my lips chapped and bloody, even with no warmth I could feel the ferocity of the sun piercing into the skin of my bare knuckles.

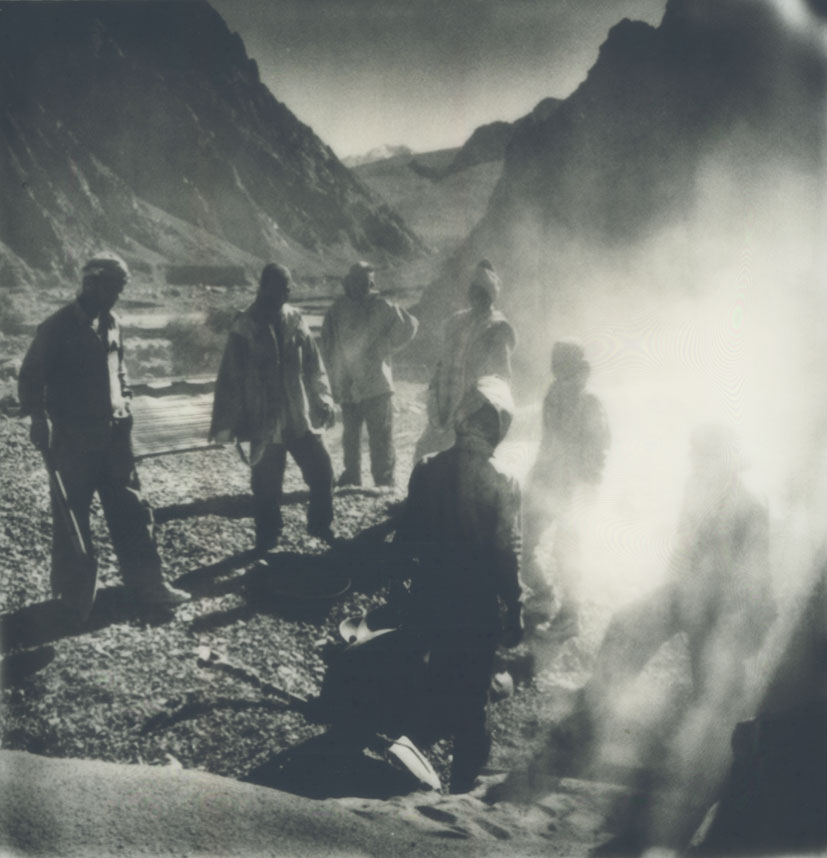

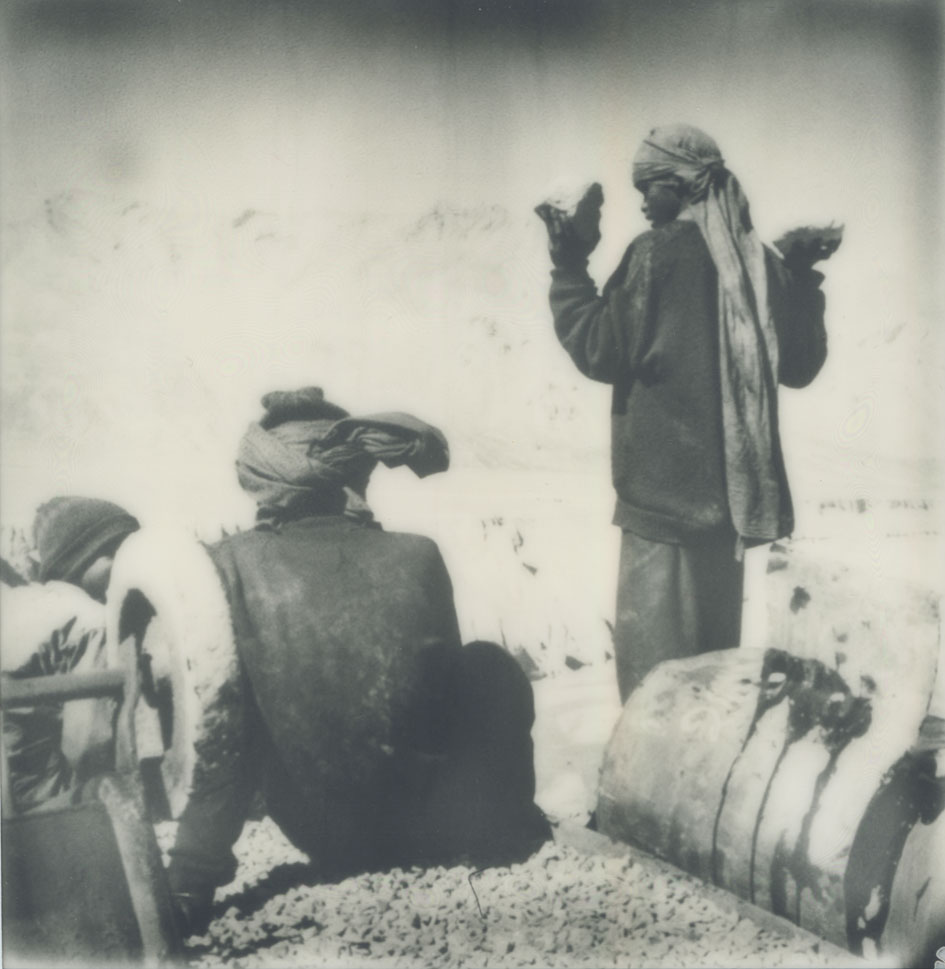

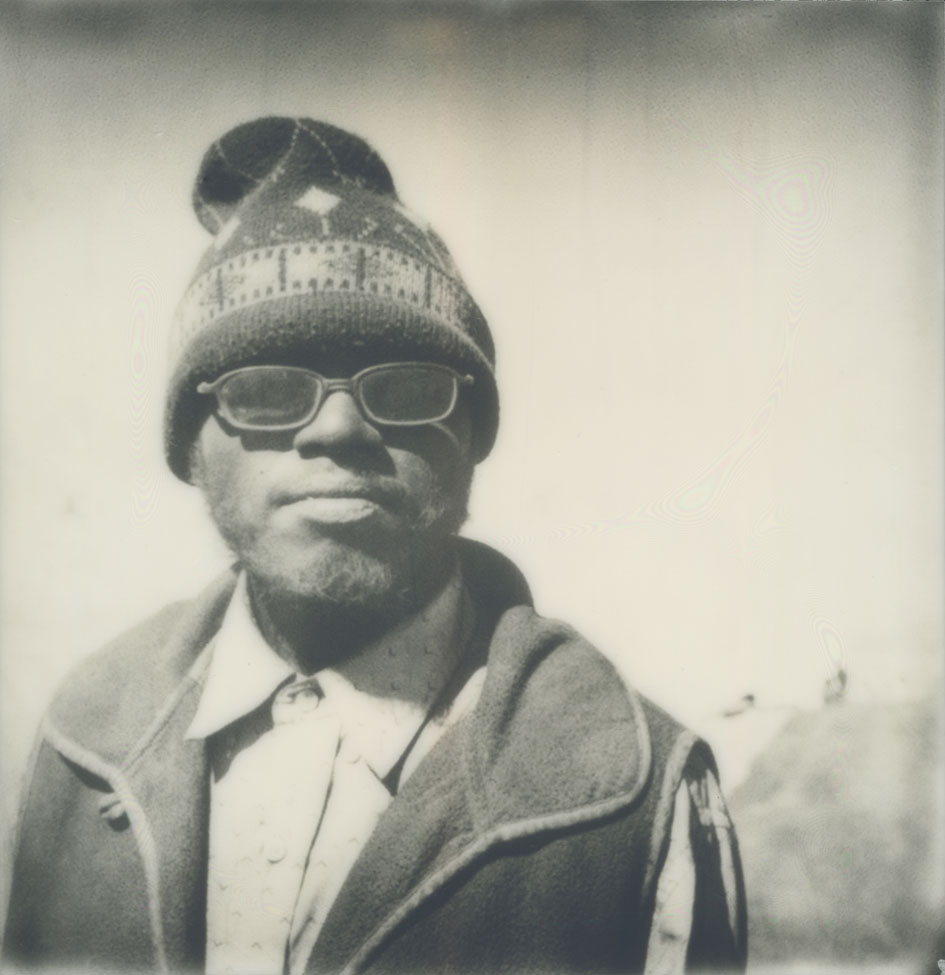

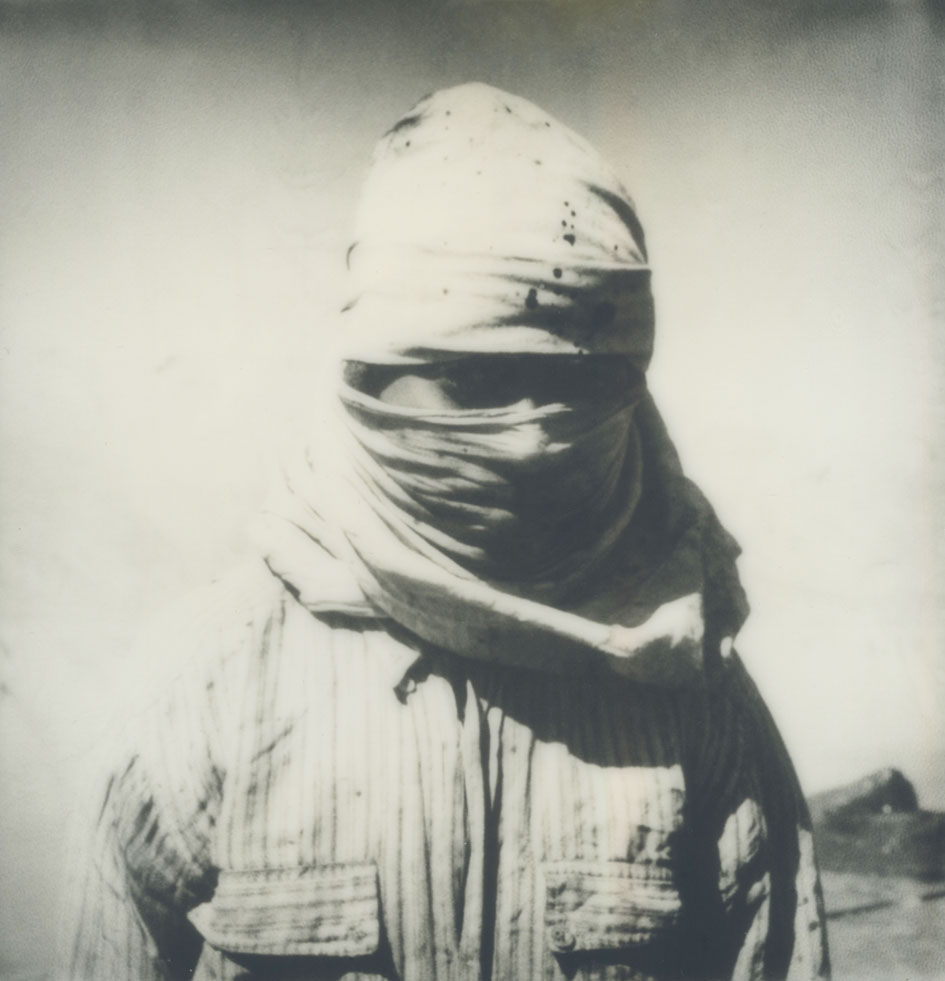

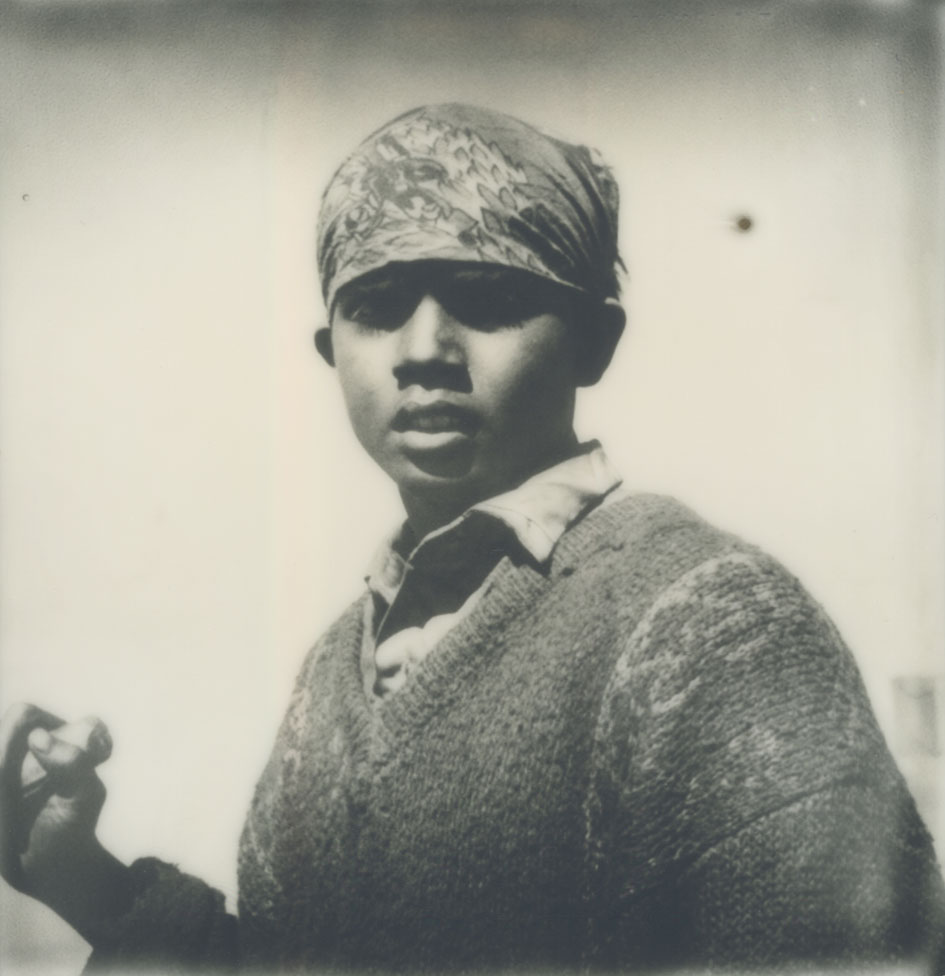

Hitchhiking allowed me the benefits of stopping whenever I desired, I would give a loud knock onto the cabin roof that would hopefully be heard over the roar of the engine and the truck would stop and I’d continue on foot, often to the bafflement of the drivers. This I did when we passed through our first encampment of workers; these workmen, shrouded in smoke from the burning barrels of tar, faces veiled in protection against the elements and the dust, whose eyes coolly and unflinchingly followed the stranger walking amongst them. Like the landscape that surrounded them they held a beauty, a dignity and a hardness unparalleled by any of my previous experiences. Unsmiling, yet holding a deep and silent strength, they gathered around me as the truck pulled away.

Unable to communicate with words I began trying to communicate with gestures; after a decade spent living amongst people of different languages, none that I can honestly say I’ve managed to master past a few friendly phrases, you come to realise that there is a communication that happens beyond words, it involves patience and subtle observation, I’ve always found it remarkable what can be understood from the simplest of body or facial expressions. Though this time it wasn’t hard to see that they looked upon me and my clothing, which I’d purchased just a few days earlier at a second hand market in Manali, as an anomaly with much comedic value - my clothes were ill fitting due to my height, my ankles and wrists protruded from these garments, my shoes were an old pair of Converse I’d had for years and were split at the sides offering little to no protection in this terrain - I was ill equipped and this was apparent.

I’ve always found that the Rolleiflex as a camera is a great ice breaker, so old and mechanical it holds a fascination that allows a starting point for communication when no words are available, I carry it almost permanently around my neck wrapped in a scarf and unveiling it and having them to look through it did just this.

Though my first impressions of them were of a hard, wary and unsmiling group, laughter quickly ensued, guards dropped, and I was invited to have chai and I shared what little provisions of biscuits I had.

I ended up spending around six weeks going up and down this road, visiting various groups and staying at roadside camps; I met the wives and children that made up the families of this workforce; I came to see the hardship and tried to understand the conditions that would drive a family to live this way. I saw the sadness, the strength and the deep resilience they held in the face of so much adversity, in such a hard landscape, working to maintain a road amongst mountains that rise above the clouds and touch the sky. - Sebastien